Nano Lopez: Sculpting the Mysteries of Nature, Technology and Folklore

Byline: Laura Blum

Walla Walla, WA -- All art is quasi-autobiographical, though for sculptor Nano Lopez, his own stirrings -- like the creatures he conjures -- are pure mystery. During moments of inspiration, the Bogota, Colombia native produces his fine art bronzes with the faith of intuition. "I do this stuff and I don't actually know why," Lopez recently told thalo.com from his studio in Walla Walla, Washington, where he has been living and working since the eighties. "The concept develops later, when I try to understand why it happened."

In recent years, Lopez has had to gin up those insights for a growing audience of patrons and admirers. Blame it on the "Nanimals," his whimsical animal pieces that have taken off in private collections, art galleries and public art venues around the world. Studded with adornments from nature, technology and folklore -- even from Walmart -- these playful beasts could achieve camouflage in a steampunk jungle at the edge of a street fair. Consider such signature pieces as Philippe III Jr., the prancing camel with jugs, fish and gears to help quench his thirst, or Elizabeth, the 6'8"-foot ostrich decked out in doo-dads and rolling a jaunty cogwheel (as seen in photos 1 & 2). Another choice item is a dragon outfitted with a fire-extinguisher and an ice-cream cone (as seen in photo 3). Davian's disruptive coloration and countershading blend in perfectly with the fevered imagination of his creator. With Lopez's twinkling eyes and wizard-style beard, he himself could have sprung from an enchanted forest.

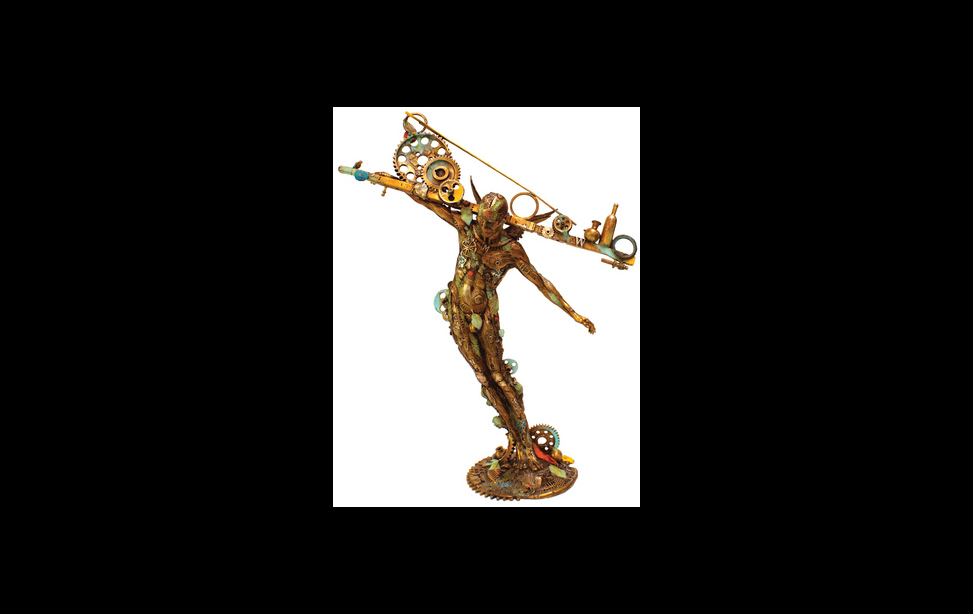

All this molding and texturing takes time. Like his distinctive human figures (as seen in photo 4), Lopez's Nanimals come by their storied forms and surface patterns through a laborious multi-step process spanning on average four months. Watch the 58-year-old artist at work here, and read on to dig deeper into his creative world.

thalo: What's your attraction to mystical art?

Nano Lopez: Everything is very magical and mysterious, so in that sense everything is sacred to me. Anywhere you direct your eyes, it's like zooming in on a world of wonder and magic. As I get closer to the microscope, I get closer to the molecules inside. The macrocosm is similar to how the microcosm works. Art is paying respect to that mystery. The only word I have to describe that mystery is "God."

th: Do you see a relationship between your exposure to Colombian folk art and your ongoing fascination with chimerical animals?

NL: I don't see it clearly, but I'm sure it's there. I think of Colombia as a lot of beautiful nature. Probably the main relationship with my work is about the richness of nature and the people.

th: How does your work incorporate imagery from Colombian markets?

NL: It's this subconscious imagery that, to me, makes Colombia rich. I get this inference of Colombia to this day: the donkeys loaded with stuff, the horses toting stuff. That's the nature of the Colombian people that you used to see a lot and that has influenced me to this day. It has to do with that imagery that I have from my childhood -- the colors, the richness, the ambiance (as seen in photos 5 & 6).

th: What were some of your formative boyhood experiences with nature, especially with aquatic life?

NL: My father liked to take little excursions all over the place. When I was about 10 years old, we took a big canoe trip along the Amazon River. It was a very cool experience. We'd wake up in the mornings and look for tracks of turtles on the beach and see where they'd nest. I'd dig there and find lots of eggs. It was a rich experience that left me with a deep impression of nature. A few years later my father took the whole family canoeing for 15 days in Amazonia. We went down the rivers in the region, and we went fishing with the locals. Whenever we wanted to camp we'd look for a place to pitch our tent, wherever. It was a beautiful and very real experience.

th: Who besides Mother Nature were the protagonists in your early experimentation?

NL: My grandmother did sculpture as a hobby. She was a housewife, but her house had lots of classical paintings and sculptures that she brought from Europe. She also did ceramics and painted with oils.

th: How important have the Masters been to your mature process, including Michelangelo’s sculptures and paintings?

NL: Very important. Michelangelo is my total hero, far more than anyone else. Leonardo was cool, but Michelangelo was my main focus. He was already a big influence on me in high school. Because of my love of human anatomy, I was investigating muscles and bones. I've always loved the way we are built, the aesthetics of the musculature. Everything is alive.

th: Were you also particularly inspired by the sculpture of Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti?

NL: After Michelangelo, Giacometti and Rodin are probably the main two sculptors I like. Giacometti's elongated figures were very interesting to me early on. As a young artist you're always searching for a style that reflects your own expression, something you haven't seen before. A contemporary sculptor whose work attracts me is Stephen De Staebler. I like the organic feeling of his work.

th: Looking back on your experiences in Europe, what did you gain from assisting the sculptor Francisco Baron in Spain and from taking classes at the Superior National School of Beaux Art in Paris?

NL: Paco Baron was a very well known sculptor in Spain at the time (late 70s). We did a lot of carving in granite and marble. We also worked a lot in bronze and stainless steel. Working directly like that deepens your knowledge of the process. It enriches you in a different way from going to school, though both experiences were important for me. What was especially interesting about Paris was the kind of environment I had around me. I wasn't there to get a degree, but I liked the exposure to different kinds of art and artists.

th: How did you move from classical forms to fantastical images -- and from organic to manufactured textures ?

NL: The story of the textures and forms follows a certain chronology. From Michelangelo I was able to develop my love for human anatomy, for how things work in intricate detail. I tried to find new ways of expressing this from ages 20 to 25. That's also when I started to become more fascinated by nature and how everything works. I was inspired by the equalness of the miracle of all life, of all beauty, at all levels. The miracle of a human being is the same miracle as a piece of grass; an animal is no different than a piece of grass. Philosophically, animals are not beneath us. It's around the time that I began embracing this philosophy that I started to introduce organic life in my work.

th: How?

NL: I started to bring in rocks and bark from trees to blend with my representations of human anatomy. Or I'd also try to make the texture look like mud. That was the beginning of my work with the human form and force, which occupied my first 20 years. Animals came later. At first I introduced organic life into the human life form, linking fertility to human nature. Then, working with the human form, I started to incorporate gears. And with the gears came glass, letters, steel -- whole city scenes from modern society. So the chronology was from human form to organic textures to gears.

th: What especially compels you about gears?

NL: Machinery is the creative side of humankind, so gears represent creative expression. Every time we build a machine or a gear, we solve a creative process. The man-made objects in my work celebrate human imaginativeness. That's why the gears attract me a lot.

th: In what way do they attract you aesthetically?

NL: My attraction is first of all intuitive. I'm interested because I'm attracted and then I understand why. The gears are circlular like planet Earth. Anything that is circular has strong symbolism. All of these man-made elements have a similar connotation in my work.

th: What do the numbers and letters connote?

NL: After the gears, I started incorporating numbers and letters, not because I'm interested in numerology, but because they have an interesting aesthetic power. They're simply beautiful. And all that they mean to us -- they connect us to humankind, communication, mathematics, literature, history, civilization. When people used to ask me why numbers are a recurring motif in my work, I used to say nothing. But I came to realize that they represent human civilization. When you see these numbers and the letters, they connect us.

th: What do you seek to communicate with your more ornamental artifacts?

NL: One of the last things I introduced to the animal figures were design-like decorations and jewels and buttons. I was simply attracted to things that were cheap and looked cool. They're almost meaningless at first, but I'm trying to understand why people like the work and my theory is that these things connect us to present civilization. A hundred years ago Walmart didn't exist.

th: How do the decorative elements serve as storytelling devices? Talk about the patterns of Sherlock the Welch terrier and Alberta the sheep (as seen in photos 7 & 8), for example.

NL: Well, in the case of Sherlock, he is a private investigator, so he carries with him a magnifying glass, a little hammer to break things and some tubes of chemicals to test things (as seen in photo 9). He has a pipe that he doesn't smoke, but he thinks he looks pretty cool with it, and he has a peace symbol because he's a peace activist. Alberta is a traveler and has collected things from all over the world. She was in Mount Vesuvius in Italy, where she got that pot for her back, and she loves long walks; in fact she has just returned from a walk that took her all the way to Cadiz, Spain. Her main pelt is made out of cauliflower (as seen in photo 10). Scales the fish is in love with her and is giving her a kiss, but Alberta doesn't know quite what to make of it.

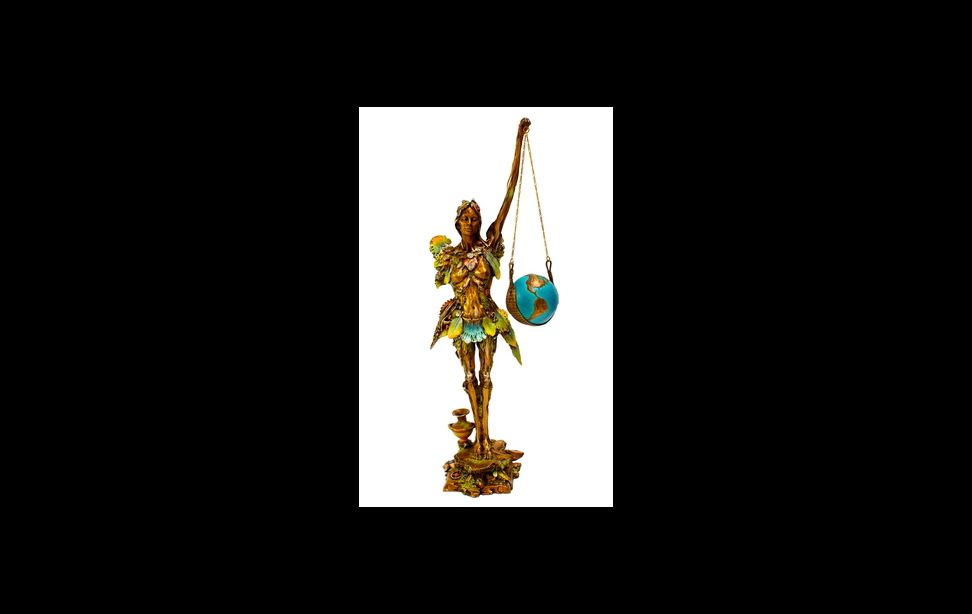

th: I see. You've been known to say that your human sculptures are self-referential and don't represent anything. Can you elaborate?

NL: I never wanted to do "the rich male of the 50s" or "the Chinese human" or "the American human." In my figurative work you do see Maria; there it's very much "the female," because she represents fertility (as seen in photos 11 & 12). She's the giver. But other than that, I don't like to be specific in history. I like humanness, human souls. This is a mysterious feeling. I'm not interested in representing someone doing a specific action that confines you to something. It's not about, "Oh yeah, it looks exactly like a man throwing a rock." I try to be universal. That's what I always felt about Michelangelo's pieces: they were not a representation of a specific act. To me the power came from inside them. His work is so powerful that the piece has a life of its own.

th: In your own work, how do you know when a piece has "a life of its own"?

NL: The piece has to have enough power about it that it convinces you, itself. It's its own personality, its own individual being with its own life force. I don't want you to like it because it looks like something else, but rather because it is its own self. If I'm doing a horse or a dragon, nobody can tell me what a dragon looks like. Five toes? Yeah, why not? Whenever form is weak, it's not convincing and you question it. If a piece is very strong, you accept it. You say it's beautiful, it's cool. You want to go and investigate it more. You don't question whether it would look like that in reality. When my work is strong I don't question its identity. The piece is itself and you are invited to ask all the philosophical questions, but the piece itself does not allow you to question it.

th: Some observers might say your Nanimals resemble child-like decor. Do you fear such criticism?

NL: I question myself sometimes. When I first started doing Nanimals 10 years ago, I was frustrated because I felt they were shallow. For 30 years I was doing human figures. It took me 30 years until anybody started buying the work. The galleries are divided into two catergories: avant-garde and conceptual as opposed to commercial and decorative. I would bring my human figures to the conceptual galleries and they would find them too traditional and figurative. And then I would bring my figurative work to the commercial galleries and they would all find them too harsh. The organic texture on my figurative work was associated with dying and decaying. But it was the opposite; it was life. My work with the human body was all about the human condition, about how fragile we are. That was the deeper subject matter.

th: Where did you ultimately find a market?

NL: People who best understood the work were from the medical field. Doctors are familiar with the human body on a deeper level. But mostly the message wasn't getting through how I wanted it to. That's how I shifted my focus to animals, because people wouldn't take the work so personally. As an artist you want to sell to survive.

th: Why especially animals?

NL: For decades I had been making monumental work for foundries. A foundry convinced me to do a model for horse sculptures for Las Vegas. I also did a cat, with very loose textures. These weren't deep in my heart. I was doing them to find something different. Visually the work wasn't boring, but it didn't really say much. The cat started selling like crazy, much more than the figurative work.

th: Necessity being the mother of invention, how did you start to see new possibilities here?

NL: At first it was challenging to discover the textures. Then I started to have a very strong change in my relationship to the animals. Eagles and bears are usually depicted in aggressive ways; or often you'll see lions attacking deer. It didn't interest me to depict animals killing animals. What interested me was the innocent quality (as seen in photos 13 - 15). There I started to have a deeper connection with the Nanimal scultpures I was doing.

th: So innocence took on gravitas?

NL: The sweet and trusting qualities were almost humorous. That's part of their beauty. I'm not a young guy, so the humorous side started to interest me more than the serious side. Now when I glance at them and they make me smile, I start to see the depth of it. It has to do with age. Earlier in my career, I didn't find any big value in making people smile. In the figurative work, that was never my intention. But now I find the humorous side more important -- it's another miracle and mystery on the same level as everything else in life.

th: How has your use of mediums evolved?

NL: The first human figures I did had very little color. I found the color almost offensive, as if it would compromise the seriousness of the work. This changed alongside my work with animals. Now I see color as part of the beauty of the world. But I still don't use as strong colors with the human figures as I do with the animals.

th: Do you still do enlargements for other artists, to support your work?

NL: I stopped doing that seven years ago because finally I could sell my own work enough to make a living.

Photo Credits:

Photo1: Phillipe III Jr. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 2: Elizabeth (Life-size) and Nano Lopez. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 3: Davian. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 4: Man Balance. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 5: Timothy. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 6: Detail of Timothy. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 7: Sherlock. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 8: Alberta. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 9: Detail of Sherlock. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo10: Detail of Alberta. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 11: Maria Mundo. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 12: Maria Alma. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 13: Bobby. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 14: Foxy. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.

Photo 15: Olivia. Photo by Nano Lopez courtesy of Nano Lopez Studio.