Stalking Salinger

For three days, a man with a camera hid in the woods of Cornish, New Hampshire. Peering through wooden fence slats, the photographer withstood sleep deprivation and a nascent case of pneumonia for a glimpse of his elusive subject. On the third day, a figure emerged. A weary, white-haired J. D. Salinger came outside to walk his dog. The shutter clicked six times, and the photographer slinked away, triumphant.

This is one of many stories compiled in Shane Salerno’s new documentary film “Salinger” and companion book of the same title. Both film and book have generated quite a buzz, promising revelations about Salinger’s notoriously private life. The real hook, however, is a long-awaited answer to the biggest question of all: what, if anything, was Salinger writing during his decades of seclusion? The already dramatic film score escalates to comic proportions as the existence of several unpublished works is confirmed, along with plans for their staggered release from 2015-2020.

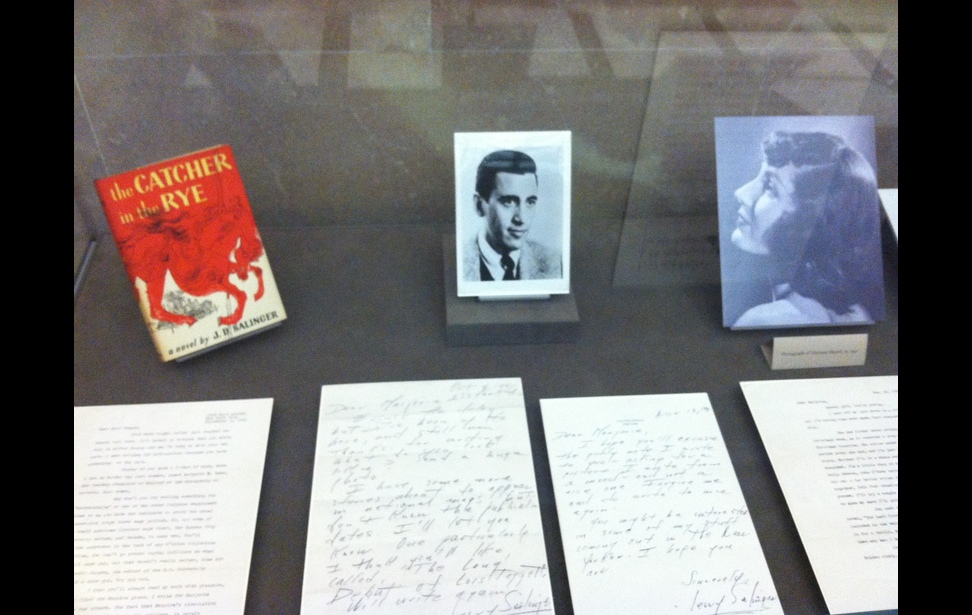

Salinger’s name has become ubiquitous in the past month, appearing on subway billboards (as seen in photo 1), bookstore windows, and all over the Internet, where film and book reviews abound. He’s even been the subject of museum exhibitions, including “Lose not heart: J. D. Salinger’s Letters to an Aspiring Writer” at New York’s Morgan Museum & Library, which presents never-before-seen correspondence with aspiring Canadian writer Marjorie Sheard. The display sheds light on the early years of Salinger’s career and contributes yet another name to the list of young women with whom he had epistolary relations (as seen in photos 2 - 4).

This hype is testament both to the zeal of Salerno’s marketing scheme and to the profound impact Salinger’s works continue to have on the American psyche. It is also precisely what drove Salinger away from the literary limelight back in 1953.

The publication of The Catcher in the Rye brought Salinger instant celebrity, confirming what he had always known—that he was destined to be a great writer, the best since Melville, as he unabashedly proclaimed. Salinger was well prepared to accept recognition for his writing. That was long overdue. He was far less enthused, however, by the deluge of attention released upon his own person.

Holden Caulfield, in all of his adolescent angst, gave voice to a generation disillusioned with phonies. “Yes! This is exactly how we feel!” the American public rejoiced, having met a character who got them, who spoke their language. You feel “so grateful to him, and you want to go find him,” says Philip Seymour Hoffman, one of the talking heads in the film. And many fans did just that.

Strangers frequently pursued Salinger at his home in New Hampshire, convinced they knew each other intimately, that he had answers to all of their big questions. Devotees travelled winding, mountain roads, crossed a covered bridge, seeking the place where a wise man was said to spend his days hunkered down at a typewriter in a concrete bunker. “I am a fiction writer,” Salinger insisted time and again, not a sage, teacher, seer, counselor.

Salinger’s refusal to engage with the public only fueled his intrigue. The less he gave of himself, the more people wanted. Readers felt snubbed, deprived of something they rightfully deserved. How dare he befriend us, give voice to our innermost thoughts, and then take to the woods, leaving us exposed and alone?

Amidst the current buildup over Salerno’s film, perhaps it’s time we turn a critical eye on our own insatiable curiosity. How many interviews, how many pictures of Salinger walking his dog, will it take to tease apart the man, the myth, and the legend? Can it be done? And, if so, what would be gained?

No amount of research could fully resolve the enigma that is J. D. Salinger. Despite our best efforts, he remains a bundle of contractions. On one hand, he was an everyman—a poker-playing, fair-going next-door neighbor, on the other, an elusive, mythical figure. He was a great egoist who sought anonymity. He was a man with a vocation, a divine calling that ploughed over everything in its path.

As we take the skeletons down, one by one, from Salinger’s closet, we find that they add up to just that—a pile of bones. The story we have to live with is the one we piece together for ourselves.

One can’t help but wonder what Salinger would have to say about all of this. When he was finished tearing down posters and sputtering profanities, I’d like to imagine him personally replacing each and every copy of his biography with a work of his fiction. He’d greet theatergoers as he once did fanatics in his driveway. “I’m a fiction writer,” he’d explain, wearily.

When we’ve tired of reading Salinger’s letters, we’ll reach once again for The Catcher in the Rye, for a familiar voice to keep us company as we tick away the days until 2015.