Please Do Not Touch!

PARIS, FRANCE -- The recent exhibition at the Musée Quai Branly in Paris entitled, Aux Source de la Peinture Aborigène, was dedicated to the aboriginal art movement which was born in the 1970’s in the Aboriginal government reserve in Papuyna. Over 200 paintings and 60 objects which have never before been exhibited in Europe were shown. A number of two dimensional aboriginal paintings with different levels of relief also formed part of the exhibition in a tactile studio, and enabled those who are blind or have visual deficiencies to experience the beauty of aboriginal art.

Aborigine culture and way of life is inextricably linked with nature and ‘tjukurrtjanu,’ dreaming. Dreaming refers to the time when ancestral spirits visited the earth and created the rivers, animals, flora, and, in fact, nature itself. The ‘dreaming’ of individual aborigines depends on where they were born, for example, the dreaming of the Aboriginal artist Abie Loy Kemarre who was born North East of Alice Springs, includes Bush Hen Dreaming and Bush Leave Dreaming (as seen in photos 1 and 2).

The richness of Aboriginal art is derived from the symbols that are used, which the uninitiated are often unable to decipher. Some of the objects shown in the exhibition included wooden shields and knives decorated with traditional motives. Aboriginal art throughout time has been manifested in diverse ways in harmony with nature including rock painting, ceremonial body painting, and sand painting which recount their ‘dreaming.’

The 1970s was a time of social and economic upheaval for the Aborigines, despite the fact that Australia was their native land, they were often the recipients of unacceptable legislation and behaviour by government authorities and treated as second class citizens. Conditions in the government reserves were very rudimentary and pressure was put upon aborigine communities to abandon their traditional culture and beliefs.

However, in 1971, in the Government reserve of Papunya a teacher arrived named Geoffrey Bardon. Although he was initially employed to teach social sciences to the children he quickly encouraged them to create ceremonial art. The elders of this community watched closely what was going on, and they soon asked Geoffrey Bardon if he could supply them with paint and paintbrushes so that they too could express their ceremonial art.

Very quickly seven men who were initiated in the dreaming of Honey Ant created a mural on the wall of the school which was to be entitled, ‘Honey Ant Dreaming.’ This lead to a men’s painting group being formed which was made up of thirty five men. They painted in what they called, ‘The Great Painting Room’ which was in fact the town hall. There was a very special energy in this painting room. The men were joyous as they discovered new materials and were able to put onto canvases their stories, ceremonies and dreaming. There was a celebratory nature to these moments. The men sung as they worked and were perhaps also symbolically celebrating the fact that they were ‘reclaiming’ their land, their stories and their dreaming.

In 1971, another important event was to take place when Kaapa Mbitjana Tjampitjinpa won the joint first prize at the Alice Spring Caltex Art awards for his painting ‘Men’s Ceremony for the Kangaroo.’ The triumph of Kaapa and the encouragement of Geoffrey Bardon was a catalyst which enabled the aborigines to transform their dreaming and ceremonial motifs into a rich new art form through the medium of painting.

Geoffrey Bardon had an enormous empathy with the aborigine community in which he was working, however politicians of the time were not ready to accept that aborigines should be accorded the equal rights that they were due. Sadly, in 1972 Geoffey Bardon was sacked for ‘creating disorder.’ However, he had started an artistic outpouring which thankfully could not be stopped, and as one of the painters Long Jack Phillips Tjakamarra stated in 2010,’ We started it like a bushfire, this painting business, and it went every way, north, east, south, west.’

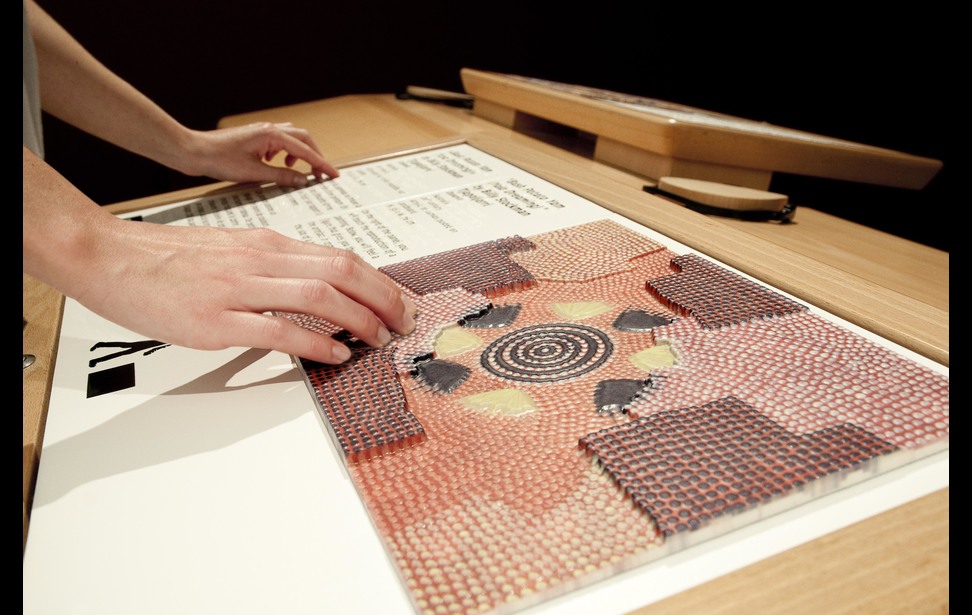

As a champion of equal rights we can only imagine that Geoffrey Bardon would have wholeheartedly supported the work of Alain Mikli who is the founder of Alain Mikli Interntaional. Alain Mikli was struck by the fact that the words, ‘Please Do Not Touch,’ are words that we often see in museums. This is of course, often understandable, some works of art are fragile, unique and worth millions. However in France, Alain Mikli, was troubled by this and he asked himself how someone who is blind can experience the beauty of a work of art if they cannot touch it. He therefore decided to finance reproductions of original works of art in two dimensions with different levels of relief.

As a result of Alain Mikli’s financial support, a tactile studio was assimilated into the exhibition of Aboriginal Art in the Musée Quai Branly to enable those who are blind or have visual disabilities to access works in relief,(as seen in photos 3-5. This tactile studio displayed four works of art by aboriginal artists including, ‘Womens Dream,’ by Ronnie Tjampitjinpa, and ‘Snake Dreaming’ by Warlimpirrnya Tjapuljarri. Each two dimensional reproduction was accompanied by an explanatory text in brail, and an oral commentary which could be accessed with headphones. The aboriginal paintings which were chosen to be recreated in two dimensions are paintings which make up part of the permanent collection of the museum. This means that the two dimensional reproductions will stay in the museum and those who are blind can continue to experience the beauty of aboriginal art.

Photos 1 and 2 Copyright Abie Loy Kemarre/ www.artsdaustralie.com

Photos 3-5, Copyright Alain Mikli International and Musée Quai Branly, Paris