Expect Awe: The 30th Sao Paulo Bienal

With a strong thematic vision, one of the most venerable international art exhibitions flaunts its relevance in its 60th year.

SÃO PAULO, BRAZIL – With 3,000 works by 111 artists, the thirtieth São Paulo Bienal is a truly massive event that—for serious art lovers—requires numerous visits and a great deal of time. Returning to the undulating ramps and curvaceous interiors of the Oscar Niemeyer-designed three-story pavilion inside the verdant oasis of the city’s beloved Ibirapuera Park, the 2012 version of the international exhibition displays an overwhelming amount of material to consider. Entitled The Imminence of Poetics, the curators have designed an impressive blueprint for the show, leading attendees through a labyrinth of works that communicate between each other as well as with neighboring works of different artists. The intention of such considered placement of the pieces—according to the exhibition’s literature—is to establish a “discursive apparatus in which bonds prevail”: this lofty goal based on viewer’s expectations (which are referred to as “imminence”) and the transformative language of the arts (“poetics”) is by no means the simple cliché of art world PR fluff it might otherwise appear to be. Indeed, the monumental scale of one of the oldest shows of its kind (second only to Vienna) succeeds in its ability to engage the viewer in its many intimate nooks, endowing this milestone edition of the Bienal with a gripping power often absent from other likeminded and extensive presentations of art.

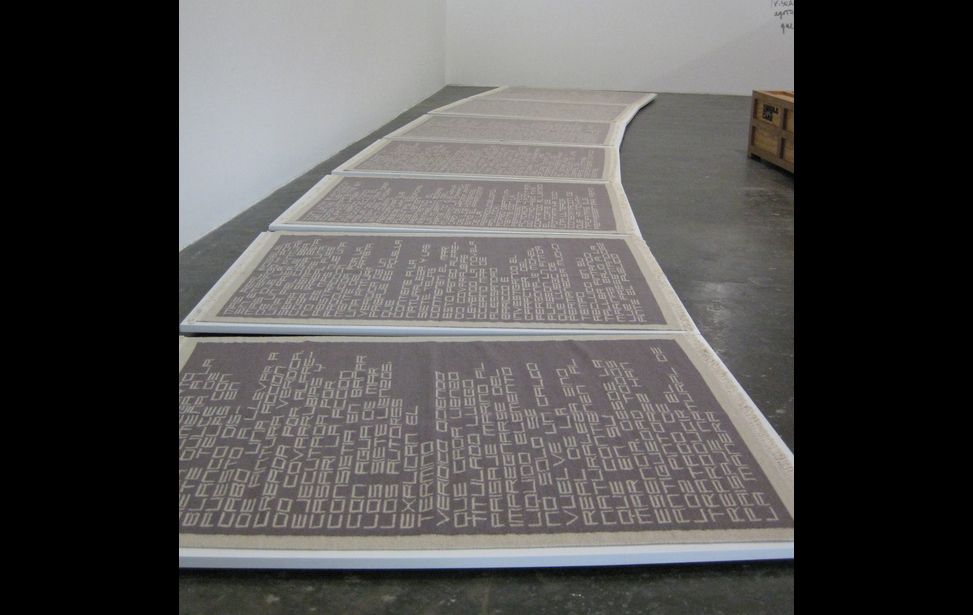

Beginning with an expanse of the pavilion’s ground floor, American-born, Parisian artist Sheila Hicks’s fabric-based pieces blur the line between fine art and folk crafts, with colorful coils snaking around wooden frames and enveloping objects like clocks and notebooks (as seen in photos 1 and 2). Her vibrant, tactile collection sprawls through its allotted space, giving the viewer the sensation of having entered a busy weaver’s workroom, and thereby making a statement about the importance she places on her chosen medium of textiles. Located nearby, the one-man collective of Peruvian artist Alberto Casari known as PPPP (Productos Peruanos para Pensar) comes across more explicit in his overarching working concept of art’s precedence over artist, demystifying the romantic notion of the artist as the sole, subjective originator of a piece’s artistic meaning. As a result, in his series of seven handmade llama wool carpets, La alfombra Villacorta, (as seen in photo 3) he gives a third-person account of another one of his works located on the opposite wall as if his hands had no part in the creative process. Here, PPPP offers craft as an artistic political statement.

In the same “cluster” of the show (as delineated by the literature), the yellow umbrellas and vertical flagpoles (as seen in photo 4) of Brazilian artist Alexandre da Cunha’s Landmark II uses fabric to link it to its nearby artists, but employs hard metal, recalling more traditional sculptural elements, as found in the comic and sharply horrific works of Cyprian Savvas Christodoulides. Pieces such as the glass-bubble blowing (as seen in photo 5) I Have Got Something to Say to You (Girl With Bubblegum), and the literal He Hung His Artwork over the Radiator to Dry, with its acrylic paint on paper hoisted above an actual radiator, are heavy on the irony. But the comedic take made obvious in his titles also allows for more sinister laughs: Suddenly… depicts a porcelain figure sitting atop a water tank being attacked by birds (as seen in photo 6), while the oil paint-soaked wooden head meeting glass (as seen in photo 7) in Look He’s Fallen Flat on His Face portrays a gruesome, bloody accident with the viewer positioned as the gawking rubbernecker capable of the detached reaction found in the title.

Ascending the pavilion’s ramps, the scale of the art expands on its higher floors with installations like the mountain of concrete, fabric and soil (as seen in photo 8) by Brazilian artist Thiago Rocha Pitta, the mechanical contraptions of deconstructed tricycles by L.A. artist Dave Hullfish Bailey, and the pastiche corners that recall punk rock teenage bedrooms, architectural models and ornate religious shrines constructed by deceased German artist Anna Oppermann (as seen in photo 9).

Contributions also charm other senses. Notably, the audio installation work of Brazilian Paulo Vivacqua’s The Triple Ohm, with its speakers emitting tones into pipes (as seen in photo 10), and Interpretação, his playful ghost orchestra pit of music stands outfitted with speakers and small drawings symbolizing the playback sounded, inviting listeners to hover over each stand momentarily before stepping quickly to the next one.

And while no less attention and praise is warranted by the contained chaos in the paintings of Lucia Laguna (Brazil), the deceptive ink drawings of Eduardo Stúpia (Argentina), the rich, natural photography of Fernando Ortega (Mexico), or the captivating paintings and bronze work of Andreas Eriksson (Sweden), ultimately, some of the Bienal’s most striking pieces are video-based, with important film installations from L.A. artist Ilene Segalove and Canadian director Guy Maddin.

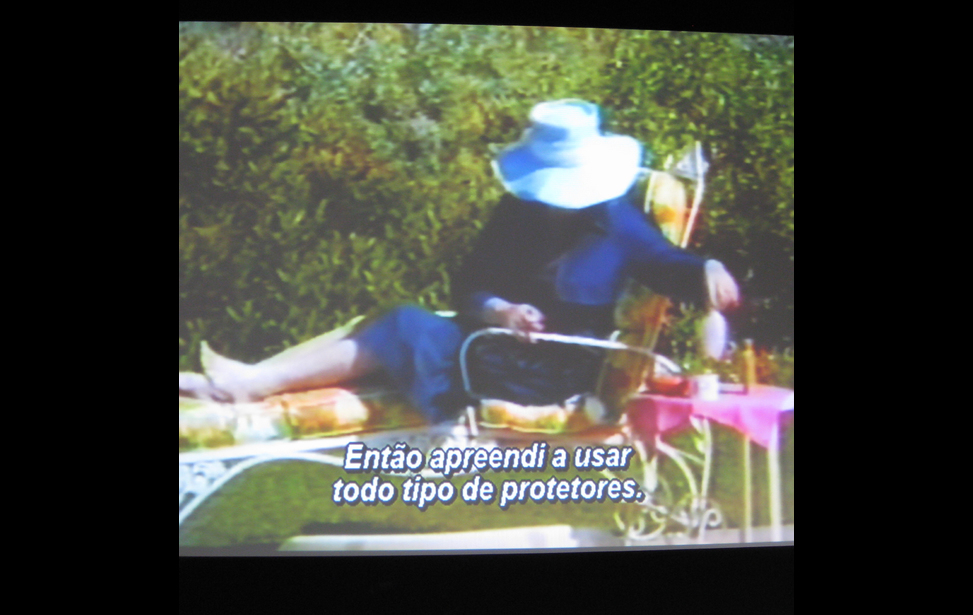

The Mom Tapes, Segalove’s primitive VHS recordings taken between 1974 and 1978, follows her mother as she opines on her home, her health, and shopping (as seen in photos 11-13). The effect is both moving and otherworldly: Segalove’s rapid-fire questions (delivered from off-camera) are answered adeptly by her mother as she moves about the domestic Californian setting as if inhabiting a series of very quiet, atmospherically-lit movie sets. The often-funny resulting 29 minute piece falls somewhere between a documentary of Segalove’s own mother-daughter relationship, a comedic, scriptless commentary on the relationship’s meaning and proof of Segalove’s artistic eye, which she would later employ in her photography.

No less strange, Guy Maddin’s installation of eleven short silent films is positioned at the Bienal’s entrance (as seen in photos 14 – 16). Revered for such films as 2003’s The Saddest Music in the World and 1989’s Tales from the Gimli Hospital, his series of projected works, Hauntings I, does not stray from his decidedly retro turn-of-the-last-century cinematic style, and as can be expected with chosen title, its films of varying screen sizes and running times often deal with macabre themes framed in melodrama: shocked protagonists confronted by the return of dead lovers looking for a second chance, a female vampire attacks a lonely man, a drowned female boxer fights her ex-husband’s new boxing wife, goddesses vie for the personification of cinema’s tributes, and a girl in a Hollywood cemetery struggles to choose a favorite between the graves of two long-deceased Hollywood stars.

Maddin’s trademark use of black comedy permeates all the films, giving an ironic distance to what would otherwise be a heavy-handed approach—but why does it open the show? Perhaps the curators felt that as the exhibition’s opening piece, the installation functions as a microcosm representative of the entire Bienal: astounding, poetic and with interpretive space for toying with that aforementioned imminence of expectation.

All photos courtesy of CM Gorey.