Cyanotypes: Non Camera Photography

Cyanotyping is a UV photographic process that produces cyan-colored prints. It is one of few photographic processes that does not require a camera, and relies on environmental sources for development.

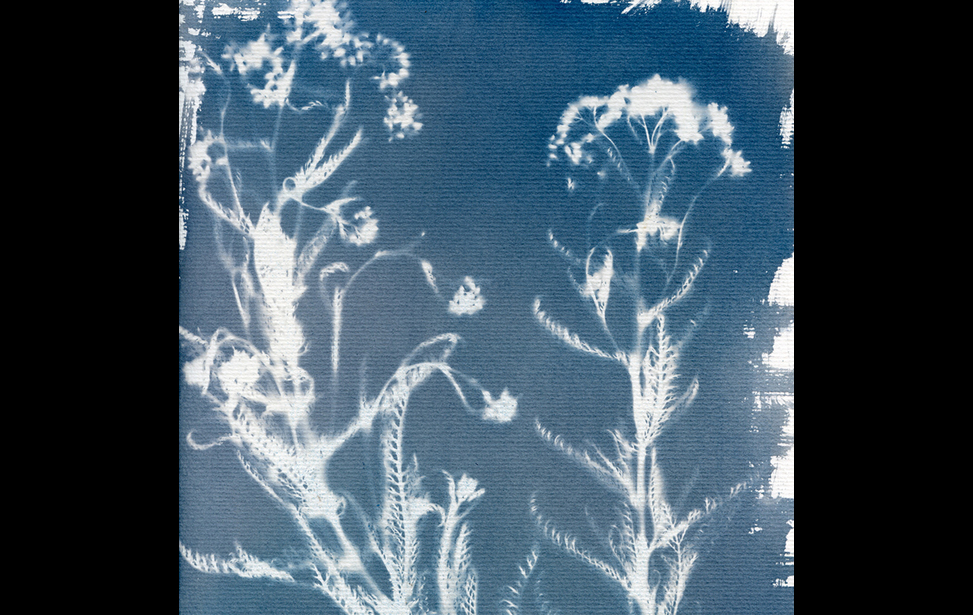

Originally conceived as a method for the creation of blueprints, artist Anna Atkins first brought cyanotyping into the realm of photography by laying algae and other sea objects over cyanotype-treated papers in order to produce eerie images. This kind of cyanotype, where objects are placed on the paper in order to obstruct light, is referred to as a photogram. In photos 1 and 2, weeds have been placed over paper to produce an outline style image.

The other common option for creating cyanotypes involves the use of a negative, which may or may not be originally created with a camera. In this method, a positive image can be produced by exposing a negative image on a treated surface to ultraviolet light (most often sunlight.) Photographers mix a solution of ammonium iron citrate and potassium ferricyanide to create a photosensitive solution. This solution can be applied to virtually any surface: paper, cloth, wood, seashells, etc. and must be applied in the absence of any ultraviolet light. The treated surface is left to dry completely in the dark. Once dry, a negative is placed on the surface, and the entire piece exposed to ultraviolet light. The result is a rich blue dye. The exact color and intensity is dependent on the amount of and length of exposure to UV light. On a sunny day, acceptable exposure is usually between 10-20 minutes, with cloudy days usually requiring more than half an hour of exposure. Photo 3 is an example of a positive image created from a negative. Cyanotype solution is most often applied with a brush, resulting in the uneven brushstrokes at the edges of the image.

Also unlike other photographic processes, there are a number of ways to create a ‘negative’ for cyanotype photography. Anyone with a computer can take an existing photo, digitally manipulate it into a negative, and print the image on transparent projector film available in sheets at office supply stores. (See photo 4.) Artists could draw or paint directly on project film as well, although it is important to remember that different media will have different degrees of opacity. The more opaque the drawing, the whiter it will appear in the final image. Very transparent media will generally appear as a lighter shade of blue than the unobstructed areas. A photographer could also use existing film negatives, or cut existing film negatives and arrange them in a collage format. Photo 5 is an example of a collaged cyanotype.

One drawback to cyanotypes is the difficulty of archival preservation. Cyanotypes don’t react well to basic environmental factors like light and changes in temperature. However, unique to cyanotypes is their regenerative behavior. If a cyanotype print has faded from prolonged exposure to light, it can often be restored almost fully to the original saturation and intensity by temporarily storing it in a dark environment. Cyanotypes are born in the dark, and thrive in the dark.

Because of the lack of expensive specialized equipment, cyanotypes are a great way to experiment. You can pick up cyanotype liquid at major photo retailers and online

Photos courtesy of:

Cyanotype Head ©Noel Tanner

The Moot Hill ©Santiago Munoz

Collage ©http://www.flickr.com/people/43545234@N03/

Weeds ©Brandon Heyer

Cyanotype Weeds ©Brandon Heyer